4.3 What do metadata look like?

Metadata always have a certain internal structure, even though the actual application can take different forms (e.g. from a simple text document to a table form to a very formalised form as an XML file that follows a certain metadata standard). The structure itself depends on the described data (for example, use of headers and legends in Excel spreadsheets versus a formalised description of a literary work in an OPAC), the intended use and the standards used. Generally speaking, metadata describe (digital) objects in a formalised and structured way. Such digital objects also include research data. In our application, metadata describe your own research project and related research data in a formalised and structured way.

It makes sense, but is not absolutely necessary, for metadata to be readable not only by humans, but also by machines, so that research data can be processed by machines and automatically. Machines are primarily computers in this case, which is why one can also speak more precisely of readability for a computer. To achieve this, the metadata must be available in a machine-readable markup language. Research-specific standards in the markup language XML (Extensible Markup Language) are often used for this, but there are also others such as JSON (JavaScript Object Notation). When submitting (research data) publications, in most cases there is the option of entering the metadata directly into a prefabricated online form. A detailed knowledge of XML, JSON or other markup languages is therefore not necessarily required when creating metadata for your own project, but it can contribute to understanding how the research data is processed.

Computer readability is an essential point and becomes important, for example, when related research data are to be found by keyword search or compared with each other. A machine-readable file can be created using special programmes. In the section “How do I create my metadata” you will be introduced to appropriate programmes.

If you are not familiar with the creation of machine-readable metadata files, you should save the metadata for your research data in a form that you can create. For example, a simple text file can be created using the integrated editor of your operating system, in which each line contains information. When doing so, consider which information is important for traceability (e.g. creator of the data, date of creation/experiment, structure of individual experimental set-ups, etc.). The categories depend on the type, scope and structure of the research data. A transfer into a machine-readable form is still possible with proper and comprehensible documentation at the end of a project or a section of the project.

Examples of metadata

In the following, a few examples will show what metadata can look like.

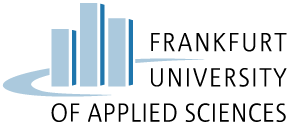

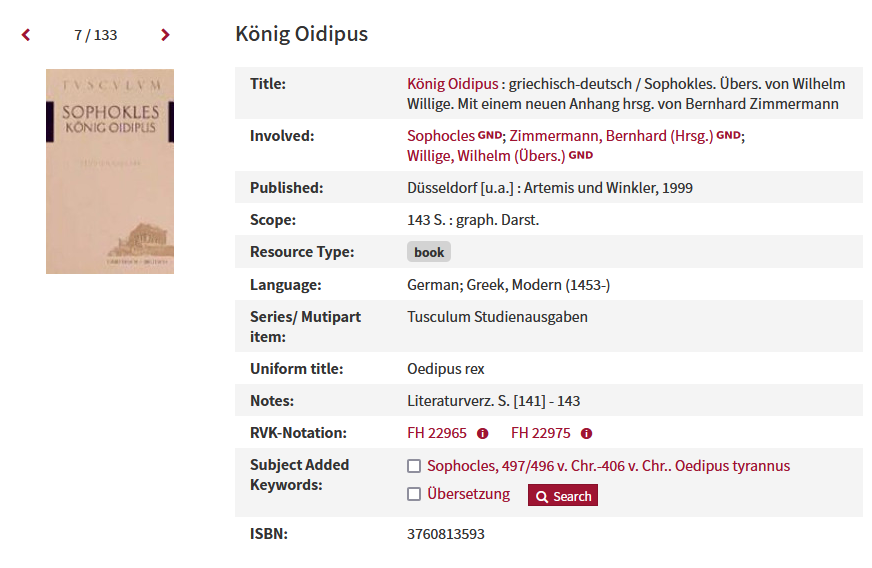

Fig. 4.1: Entry of a work in an online library catalogue (source: https://ubmr.hds.hebis.de/Record/HEB060886269?lng=en)

Figure 4.1 shows a book title as an entry in an online library catalogue in a form that you, as a member of a university, have probably seen many times before. It should be noted at this point that metadata is not a new development and does not only play a major role in the digital age, but has already been used before, for example, in the creation of card catalogues in libraries for locating books. The information listed in Figure 4.1 is also nothing more than metadata that can be processed by a processing system and read by users to obtain information about a particular book. They learn about the title, the author(s), the volume, the year of publication, the language, etc.

Although the data from the example above is probably very different from your research data, it illustrates very well the way metadata is collected. If metadata for research data were written in the way shown here, namely in a kind of two-column table, with one column containing the category (e.g. title) and another column containing the actual information (here “King Oedipus”), this information would in any case be helpful for a later researcher to understand the data. However, it would not yet lead to computer systems being able to process this data automatically.

If you have no experience at all with the creation of computer-readable metadata, it is worthwhile, as already mentioned, to use such a tabular list of all relevant data in a file (e.g. .docx, .xlsx, .txt, etc.) at the beginning of a research project and to keep it current, in order to have this data at hand for a possible later submission. Also stick to a sensible versioning concept in order to make changes in the data traceable in the course of the project (see Chapter 8).

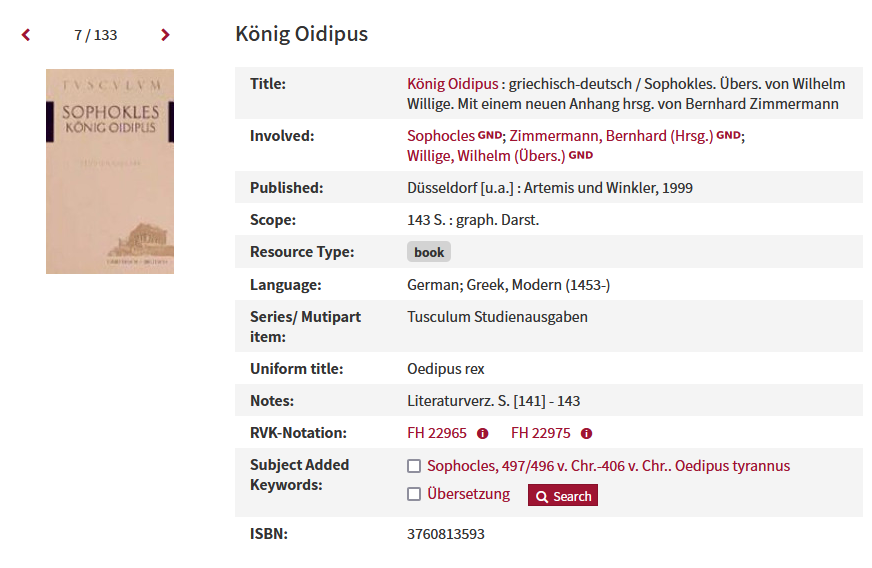

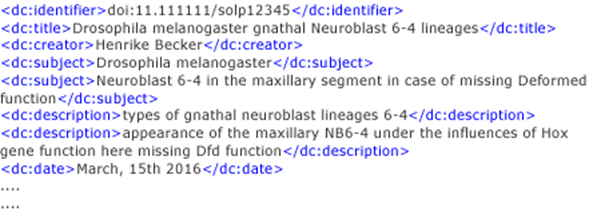

Fig. 4.2: Machine-readable example metadata according to the Dublin Core Metadata Element Set (created by Henrike Becker in the project "Fokus")

Figure 4.2 shows part of a machine-readable metadata record written in the markup language XML according to the conventions of the Dublin Core Metadata Element Set, which was first published by the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative in 1995 (more on this in section 4.4 – “What are metadata standards?”). How this can be recognised is explained below.

Everything written in blue in Figure 4.2 are elements, everything written in black is the content of these elements. A simpler understanding of this relationship can be obtained by looking at Figure 4.1: The left column contains the type of information or category (e.g., “title”, “author”, etc.), the right column shows the actual information within this category (e.g., “King Oedipus”, “Sophocles”, etc.). The relationship between the element and the content of the element is analogous, with the type of information/category representing the elements (blue font in Figure 4.2) and the actual information representing the content of the elements (black font in Figure 4.2).

A fundamental difference, however, is the structure: element names are always enclosed in less-than and greater-than signs <...>. In addition, there is an opening and a closing element for each category. The opening element can be recognised by the less-than sign < and always stands before the actual information. The closing element is recognisable by the forward slash / after the less-than sign < and always comes after the actual information of the respective category. These opening and closing elements thus practically always enclose the information content, which is easily recognisable in Figure 4.2. The information about the category is located between the the less-than and greater-than signs (e.g., “title”, “creator”). The information written in black between <dc:creator> and </dc:creator> thus gives information about the author of the respective document or data, for example. In the case of Figure 4.2, this would be “Henrike Becker”.

At this point, the other elements shown in Figure 4.2 should be briefly explained. The <dc:title> element contains the title under which the document or research dataset was published. Systems that read and display titles from a database often use the content of this element as information. <dc:subject> can occur several times and always contains a subject of the content in keywords that serve as a search basis. The second <dc:subject> element in Figure 4.2 contains a very long specification of a subject (i.e. not only keywords), which should rather be avoided in order to achieve better search results. The <dc:description> element gives a short summary of the content. In the case of text publications, the table of contents can also be placed there. Multiple entries are also possible for this element. <dc:date> contains a date, usually the date of publication. If possible, the date should be written according to DIN ISO 8601 as YYYY-MM-DD for better findability. Within this element, sub-elements (so-called child elements) can be placed, which finally give more precise information about the date, such as whether it is the date of creation, the date of the last change or the date of publication. The <dc:identifier> element is only present once and mandatory in a metadata record. The persistent identifier it contains, is assigned only once worldwide and uniquely identifies the document or research dataset. More information on persistent identifiers can be found in the following section “Which categories are important” as well as in the section “Findable” of Chapter 5.

The two letters with the colon dc: that precede the actual element name creator etc. in the elements show that the elements come from the Dublin Core Metadata Element Set mentioned at the beginning. Further information on why these two letters should or often even have to be written in front of them is explained in more detail in section 4.4 – “What are metadata standards?”

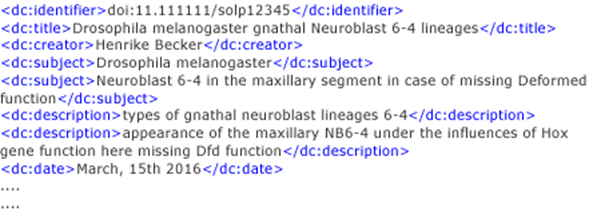

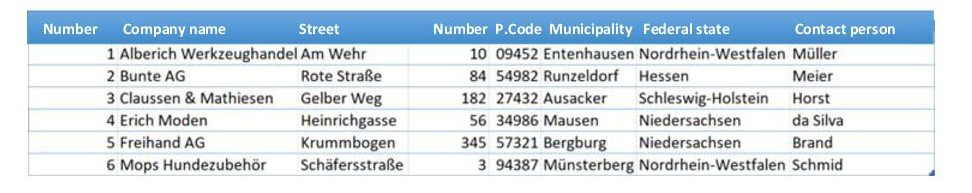

And now it's your turn. In the table shown, what is data and what is metadata? Click on the image to see the solution.

Fig. 4.3: Data and metadata of an Excel table

There are very many different categories that can and often must be described by metadata. Depending on the field and research data, these categories can differ greatly, but some are considered standard categories for all disciplines.

One category that should be present in the metadata at the latest in the case of a citable publication is the “persistent identifier” mentioned in the previous section. An identifier is used for permanent and unmistakable identification. The DOI (Digital Object Identifier) is well-known and frequently used. A DOI is assigned by official registries, such as DataCite. Metadata are linked to the document and the research data via a DOI. Research data can be cited via a DOI.

Furthermore, the metadata should indicate who the author of the data is. In the case of research groups, all those involved in the work or who may have rights to the research data should be named. The latter may, of course, include companies that may have contributed to the funding of the research. Always make sure that the names are complete and unambiguous. If a researcher ID (e.g. ORCID) is available, this should be mentioned.

The research topic should be described in as much detail as necessary. In view of the findability of the research data, it can also be useful to mention keywords that can then be used in a digital database search to achieve better results.

Furthermore, for the traceability of the research data, clear information is needed for parameters such as place / time / temperature / social setting, ... and any other conditions that make sense for the data. This also includes instruments and devices used with their exact configurations.

If specific software was used to create the research data, the name of the software must also be mentioned in the metadata. Of course, this also includes naming the software version used, as this makes it easier for researchers to understand later why this data can no longer be opened in the case of very old data.

Some metadata requirements are always the same. This also applies to the categories just listed, which are very generic. For such cases, there are subject-independent metadata standards, including the already introduced Dublin Core Element Set. Other requirements can differ greatly between different disciplines. Therefore, there are subject-specific standards that cover these requirements. You can read more about this in the next section 6.4 – “What are metadata standards?”.

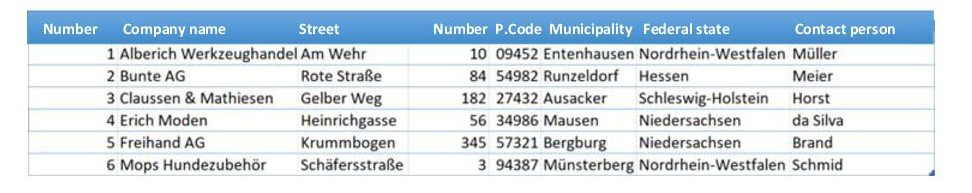

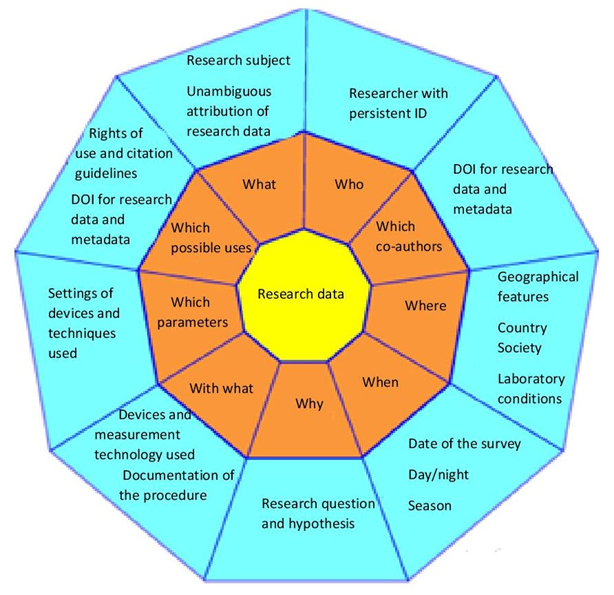

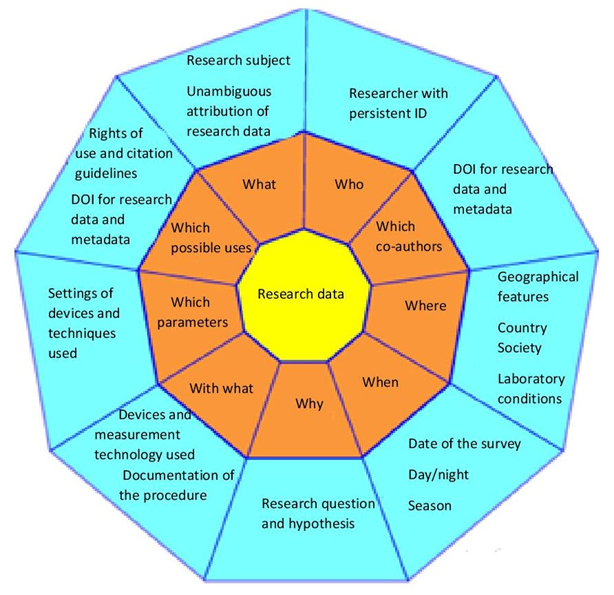

Figure 4.4 shows different categories of metadata that may prove useful with regard to research data.

Fig.

4.4: Listing of sample categories (Created by Henrike Becker in the project "Fokus")